In July of 1974, the culmination of a Captain America storyline by writer Steve Englehart and artist Sal Buscema finally hit the stands, at which time it arguably became one of the most memorable and engaging tales to be published in the title. Its plot, which all in all took a year to play out (with Roy Thomas, Tony Isabella, and Mike Friedrich assisting with scripting), spoke to both corruption and conspiracy, and essentially put this question to the reader: How would Captain America fare against a media campaign designed to turn public opinion against him? Given Cap's high standing with the public at the time, such a venture might have been considered a nonstarter--but as Jordan Dixon, alias the Viper, put it, "Never underestimate the power of advertising. For the majority of the public, 'all they know is what they read in the papers'--or see on television!" (An assessment which has since added the Internet to the list, surely.)

Dixon gets the ball rolling by phoning his crooked partner in the ad business, Quentin Harderman, and telling him to begin a campaign to discredit Cap and tarnish his name--and so to Cap's astonishment, the first public service announcement by the so-called Committee to Regain America's Principles (I'm sure you can piece together the resulting acronym) is aired.

To add fuel to the fire, Harderman (along with his accomplice, Moonstone) would also go on to frame Cap for murder, in full view of witnesses--at which point Cap refuses to be taken into custody and flees the scene.

As difficult as it is to imagine such behavior from Captain America (jeez, Cap, Iron Man managed to deal with similar circumstances without alienating the law--yet you, of all people, cut and run?), Cap has become caught up in a web where he begins to justify being both a fugitive and, later, even a thief. But by the time of this story's well-anticipated conclusion, his road has led him to the White House, where enemy forces have arrived to demand control over the entire country--and the lies doled out by Harderman's "Committee" are far from over!

To bring us up to speed, we return a bit to when Cap is still on the lam, and he and the Falcon finally catch a break in the struggle to clear Cap's name when a chance encounter with Charles Xavier and two of the X-Men establishes a connection that now factors in one of Marvel's oldest criminal organizations.

It's not quite "war" on mutants, but the Secret Empire is indeed abducting mutants in order to power a device that siphons their brain energy--a far cry from the shenanigans taking place on Madison Avenue in regard to Cap, but certainly a danger worth noting at this point.

But why are Harderman and Moonstone in bed with the Secret Empire? To gain some insight, we turn to SHIELD agents Gabe Jones and Peggy Carter, who have infiltrated the Empire's ranks and now provide Cap and ourselves with a brief history of the Empire's internal power struggles--a recap which mostly serves to pave the way for the Empire's resurgence under a new Number One.

As we've seen, the Empire goes back to the mid-1960s, when their agent, Boomerang, was sent to steal military secrets, which led to the involvement of the Hulk and the subsequent end of Number One (whom the Hulk couldn't have cared less about, a fact which escaped the paranoid head of the Empire).

As for the remaining upper echelon of the Empire, their ranks are depleted when, in a dispute with Number Two, Number Nine finishes off the lot of them (before he would later meet his fate at Gabe's hands).

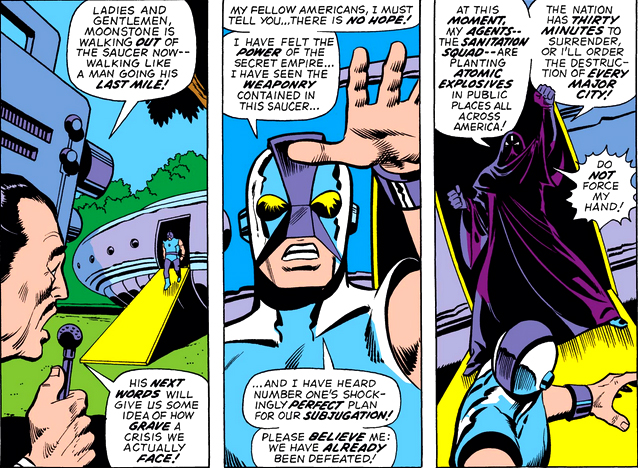

With the reconstituted Empire's involvement in this entire affair, as well as that of S.H.I.E.L.D., the stakes have been raised considerably in what appears to be a plan that goes well beyond discrediting Captain America. When the time finally arrives for the Empire to make its move, its new Number One, having already coordinated with Harderman and Moonstone, now heads for Washington, D.C. without delay. (While it looks like the Blob has lost his comfy slab and has now been wedged into the group of mutants on the disc where they remain helpless.)

But even in such a power play, the deception continues involving the new "hero" named Moonstone, who has managed to replace Captain America in the hearts and minds of the public but who now plays a crucial part in the smokescreen launched by Harderman and Number One to secure the Empire's assault on the government. But unknown to these deceivers, there are stowaways within the assault saucer who are finally on track to take their fight to the source of this conflict's planning and lies--and one in particular whose moment has been a long time coming.

Granted, even with Number One's takedown, the subsequent restoration of the image and reputation of Cap--still at this point a murder suspect and fugitive from justice--might have been a more rocky road where John Q. Public was concerned, had Harderman not stepped forward to save his own skin. Moonstone was savvy enough to seize the moment and implicate Cap's involvement with the Secret Empire--while his own status as a hero in the eyes of those who might have still been pulling for him to defeat these invaders was yet untarnished. Instead, he sings like a canary (instead of simply departing, which was well within his power)--while we learn that Dixon, however outraged by the turn of events, can at least be happy that his Viper mask apparently met otherwise stringent prison rules for the clothing of inmates.

Now. With everyone being rounded up and taken into custody, guess who was nowhere near the top of the list, despite the telling number on his hood?

The face that Cap reveals is obviously shocking for him to have seen, enough to strike at the heart of his belief in the values and virtue of his government and those at the head of it. The fallen man's identity isn't disclosed in subsequent stories; but the popular answer among those interviewed on the subject appears to boil down to "The metaphor couldn't be more obvious," a statement that Marvel editor Tom Brevoort has also been in agreement with. But to "get there"--a phrase used to indicate an effort made to reach a conclusion that seems a bit of a stretch and can't be justified--we're asked to overlook the fact that this running, hooded figure's flight to what is presumably the Oval Office is completely unimpeded by not only a host of military personnel and SHIELD agents on the scene but also any White House military guards or on-site Secret Service that would normally have been on duty and would have piled on this menacing-appearing loon like NFL tacklers.

As for Cap, we see in the next issue that he's retreated to Avengers Mansion to undertake considerable soul-searching in regard to abandoning his Captain America identity. Among all of those who offer an opinion to him as to why he should continue, only Peggy Carter's words resonated and truly struck home in terms of how important his role was--yet when those sentiments came to naught, the writing for Cap was on the wall (and on the cover).

Cap had emphatic words to say in that issue about how little trust people might have for "heroes" from now on--words he would apparently ignore in his pivot to becoming the costumed Nomad, an identity he was both comfortable in and enthusiastic about (until a tragedy following a string of Cap stand-ins forced him to reconsider). As for Englehart, the following year would mark the end of his run on the title--ten months before a certain U.S. President, mired in scandal and disgrace, would resign from office.

5 comments:

I agree with your appraisal of the Englehart-Buscema run, C.F. Englehart took the cliche of a cornball secret organization (plenty o' them around in comics) and made it relevant, but also made the whole thing suspenseful, like there was something serious at stake, there.

Not everybody digs Sal's work, I know, but the clean simplicity of it works for me. It's like a counterweight to the complexity of the plot.

A little kid could enjoy it just for the action and the pictures, which is exactly what little M.P. did!

As for (ahem) "Number One", my mother used to describe him as being almost like the Anti-Christ, the epitome of evil.

But Watergate seems very quaint, now. Hard to shock people these days, more's the pity.

I tell her that guy was a choirboy compared to...

M.P.

You make a good assessment of the Secret Empire, M.P. The irony of the Empire is that, behind the scenes, it could have been such a force in terms of insinuating itself into national affairs (and when you've reached the Oval Office, it's safe to say the world is your oyster)--yet it strove to not be so secret that it had to conceal its organization and, by extension, the identities of its members. Add to that the power plays taking place on a greater scale (even within your own ranks), and they weren't so different from their "mother" organization, Hydra.

Back in the '70s all this was just a story in a comic-book but nowadays it seems frighteningly real with the Republicans/MAGA/Qanon crowd just one step away from all-out fascism.

I agree it was suspenseful... until the end when the climax basically is "the bad guys give up because the good guys have to win."

I think Steve Englehart often had very good ideas, but his execution of them was often subpar. Good in certain ways, but failing in others that usually let me down. His Batman run is considered a classic, but he failed to make Silver St Cloud a real romantic interest for Batman. I never felt there was real chemistry between her and Bruce. He just asserted it. That's far different than many other comic book romantic interests that successfully established chemistry between the characters. His Time Travel story in West Coast Avengers where the team is divided into multiple time lines should be great, but it's let down by a completely uninteresting foe - a Lucifer knockoff and a bunch of lame goons with names like "Gila, "Cactus", and "Butte". The "Celestial Madonna" is a fascinating concept, but it's weighed down by the bizarre things he does with Mantis - he really needed to reconceptualize the character. He had a strong idea with the FF by "retiring" Reed and Sue and letting Ben be the leader. But the actual stories were extremely subpar and certain ideas like turning Ms Marvel into a pseudo-Thing just retreated territory we had been over ad naseum so we weren't moving into new ideas.

His strengths and weaknesses made him one of the stronger 1970s writers (but not one of the best), but by eighties he was in a much lower position relative to other writers because quality had increased so much.

Chris

That observation could lead to an interesting premise for a post, Colin: Which storylines in the past have proven to be prescient in inadvertently predicting future events?

Chris, that's a fair point about this storyline seemingly being wrapped up too abruptly. I can't recall the when or the where, but I seem to remember Mr. Englehart addressing something along those lines in a special blurb somewhere (perhaps a letters page, though I came up empty on that). Maybe an eagle-eyed thread reader will help us out and chime in with the answer. :)

Post a Comment