While there have been a number of Fantastic Four issues that have celebrated the book's publication in terms of the issue number itself, whether it was the 50th issue, 100th, 150th, etc., celebrations of the book's years in publication have been fewer and further between by necessity, the longer intervals being due in part to having to wait to actually reach the 20th or 30th year of publishing. Various factors would make it difficult to depend on those issue numbers as a countdown to x number of years of publication; for example, the 100th issue didn't coincide with the book's ten-year anniversary (that would have been issue #116), thanks in part to the title's first six issues being published bi-monthly.

The PPC has to date presented posts on two of Fantastic Four's anniversary-related issues--its 17th (issue #200), as well as the Fantastic Four Roast--an encore to its 20th anniversary celebration, published six months earlier. That forty-page story from 1981 was scripted and drawn by John Byrne, who had just four issues under his belt at that point and was just getting started with what would turn out to be a run of over sixty issues. Byrne's story would feature two classic FF villains, in a joint scheme that would neutralize Reed Richards, Sue Richards, Johnny Storm, and Ben Grimm, for as long as they lived--but it's the issue's parade-style cover and the story's nostalgic splash page which serve to grab the reader's attention even before our villains would make their entrance.

But by the time you've flipped open that cover, the FF have already succumbed to this master plan. And neither they nor you, dear reader, are yet aware of it.

Instead, its opening pages take us on an informal tour of the idyllic town of Liddleville, and introduce us to the story's principal characters--some of whom are not as we know them:

- Ben Grimm--former quarterback, owns a local tavern/restaurant

- Alicia Masters--Ben's wife, who in Liddleville has perfectly normal vision

- Sue Richards--homemaker, Reed's wife, and co-parent to their son, Franklin

- Johnny Storm--student at Liddleville College, trying to save enough money to move to New York

- Reed Richards--employed as a professor at U.L.--feels confused and befuddled much of the time, and often berated by...

- Professor Vincent Vaughn--the university's president, who treats Reed as totally incompetent

- Phillip Masters--Alicia's stepfather, owns a toy shop, and is a friend to Ben and the others

From the beginning, however, we're made aware that Reed, Ben, Johnny, and Sue have all been having disturbing dreams, about the same subject--all having to do with a mysterious rocket launch, and involving all four of them, with variations depending on the dreamer.

But it's only after another uncomfortable encounter with Vaughn that both Reed and the reader learn that there may be much more going on here in "Liddleville" than anyone realizes--and for Reed in particular, that door to the truth must be pried open further when he deduces that he and his partners have become victims of the Puppet Master.

Reed's drastic step results in a painful collapse into unconsciousness; but later, back at his home, his late arrival is followed by an explanation as shocking as his appearance, a story that no one is willing to either believe or accept as fact. (I'd add that Reed has his work "cut out" for him, but this is no time for puns!)

We're not privy to just how Reed manages to convince his friends of the truth of his claims--but regrettably, for Masters, that time arrives, in the form of a harsh confrontation with his "son-in-law," Ben. And once the facade is dropped, the other villain of this drama makes his presence known, in a scene of triumph which must give him no small amount of satisfaction.

And so the problem for the FF becomes: How to extricate themselves from the fate that Doom has condemned them to? Well, by all rights, this story should end here and now, since Byrne has provided a clear-cut solution for these people, if only he had allowed them to become aware of it (particularly the one person who should be aware of it). Consider for a moment: If you managed to put Dr. Doom under your control, would you have any reason to release him from that control? Especially since he would mostly likely end your life in an instant for committing such an act? We've already learned that, in order to implement this plan, Masters held Doom in his thrall through the use of one of his trademark mind-controlling puppets--yet Doom has clearly acted on his own here, betraying Masters in the process and forcing him to share the FF's downfall. Masters, then, would merely have to re-establish his control of Doom (perhaps through use of a smaller puppet he'd carried with him in Liddleville), and voilà, problem solved and everyone goes home; yet we're forced to presume that, for whatever reason, Masters released Doom after the FF had been subdued, and Doom was in a forgiving mood since he found his goals regarding the FF were in alignment with what the Puppet Master had put into motion. I suppose stranger plot contortions have happened.

The only other way out of this mess, then, depends on the FF regaining the use of their powers, which, thanks to the unique nature of these miniature "synthe-clones" they're trapped in, Reed believes is possible through the use of a particle accelerator back at the university. But one FF member, who has finally found peace and happiness in Liddleville, has decided to opt out.

It's an interesting conversation, since it brings to light something that we knew even during the days when Stan Lee scripted the book: that there were other heroes in the world who could step in and deal (or at least help) with whatever crisis the FF was facing. Lee, however, would instead have Reed responding to a feeling of hopelessness within his team with a scene like the following:

In Liddleville, Reed tries a similar approach with Ben, though Byrne's words for Reed are equally perplexing: "...we have been elevated beyond being just super heroes... We aren't just heroes. We are the Fantastic Four, and you know as well as I do just what that means." Reed obviously wants those to be the words that hit home for Ben--but what does that statement mean? For his part, Ben rejects Reed's argument, at least for now.

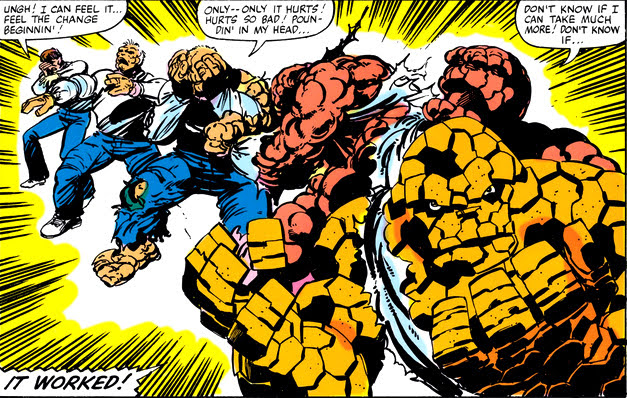

Later, though, when his partners are ready to lay their lives on the line, Ben steps up--and the Thing lives again.

With their powers restored, the four make their way out of the Liddleville set and into Doom's lab--and from there, all of them work together to configure a method of breaking the connection which channels their minds from their grown bodies to these smaller forms they now inhabit. Finally, when they're ready to act, all they need to initiate the process is the circuitry present in Doom's armor--which means luring Doom back to the chamber, and without making him aware of their plan. For those readers hoping for a final battle between Doom and the FF, the resolution to the story may be somewhat anticlimactic; for what it's worth, however, Doom himself finds that his brilliant plan has developed complications that will occupy him for some time, should he survive.

The contrast here between Masters and Doom is spot-on, at least in this one story: "What is your hatred for the Fantastic Four compared to my hopes for my step-daughter?" Of course, there were plenty of times when the Puppet Master's lust for power and hatred for the FF were on a par with Doom's--but for Masters to insinuate himself into Liddleville and the lives of the people therein, Byrne would have been obliged to table those traits for the time being. That said, it's a fair bet that Doom is wishing right now that the more benign Phillip Masters was still around, eh?

The last anniversary issue before Fantastic Four, Vol. 1, calls it quits!

Some of the book's classic inkers who pitched in for this issue!

(But only for thirteen pages! Hmph!)

7 comments:

Similar story line to something somewhere in ASM #499-500 involving Mysterio. I read the Mysterio before this Byrne tale and Byrne's is miles better. While I'm not a great fan of his artwork (no silverageness to it, and I don't mean Kirbyness) I do enjoy what I've seen of his FF plotting.

The idea of transferring human minds into robot bodies is now being seriously contemplated by crazy tech geeks. At the moment of death a person's consciousness would be uploaded to cyberspace and then later downloaded to a synthetic body which would allow that person to live indefinitely - well, that's the loony theory but putting it into practice will probably be the hard bit :D

Colin, I expect that'll be Boris Johnson's next plan after Space Command, and inexhaustible lasers.

Sorry Comicsfan, I couldn't help myself there.

Anyhow, great piece about FF #236, which really showed that whatever you think of him Byrne really knew how to write as well as draw comics (or at least the FF). Along with Miller's Daredevil and Simonson's Thor, the first half of his FF run reignited my interest in Marvel back in my late teens.

Those guys seemed so effortlessly good at what they did I couldn't understand why Marvel didn't sack all their writers, and just let the artists get on with it...

-sean

dangermash, yes, he seemed to have a plan for the FF's direction and treatment from the start (his "back to basics" approach), and it's fair to say that the book's readership responded well to it. (Though I'd be curious to see a compendium of opinions from readers as to what they felt didn't work so well for them, such as your comment on the artwork--it's always informative to get a broad perspective on the pros and the cons.)

Colin, tbh such a concept sounds a lot easier to imagine than to make into reality. Capturing a person's consciousness? Really? How in the world would one go about that? And how many of us would want to become the next Deathlok?

sean, I agree that Byrne's fresh take on the book made for interesting reading in those days. I'm not sure I'd want Marvel to hand over all the keys of the asylum to the artists, however--I wouldn't want to see another Jack Kirby discover their concepts hadn't translated so well to execution.

Ah well Comicsfan, I like solo Kirby and think he did his best work at DC in the first half of the 70s...

You're right of course to suggest that most artists probably couldn't pull off the double like Byrne, Simonson or Miller - or before them, Kirby, Steranko and Starlin - but there is something special about a comic with a single vision, which Marvel lost when they no longer had space for the writer-artist book.

-sean

Well, since you asked...

In general, I found Byrne's FF writing too inspired to cheesier elements of vintage Twilight Zone, Outer Limits, and/or Star Trek:TOS. Some plots felt so familiar that I could nearly name the TV episode that influenced him. Mostly it was just a...tone. A tone of "isn't this strange? Isn't this so very odd? What could be happening? Whip back the curtain for the revelation that will leave you gasping with shock and wonder!

Except, the aforementioned inspirations from vintage TV always left me, at best, with a vaguely warm nostalgia. All too often it left me with a "been there, seen that" discontent.

But, to be fair, he did put out some fine rootin' tootin' superhero action issues that I really enjoyed.

In this particular issue, I can only surmise that Doom and Masters were long-frustrated model railroaders. The sheer effort at making a perfect "Liddleville" world must surely have vented that yearning. Maybe they hijacked a tanker car of Pym Particles and shrunk everything they needed. Whichever the method, it was still a lot of work for such a finite project. Sooner rather than later, one of your prisoners will wander outside the town limits (as Johnny did) and meet the killer robots. The jig is up.

Some sort of "shared dream" illusion would be the obvious plot to keep the FF imprisoned, but then there wouldn't be that two page spread reveal of a colossal Doom leering down at the tiny town.

sean, your mention of Simonson is a good example of what I meant. His handling of the Mighty Thor title was IMO one of the high points of the book and beyond reproach, whereas his Avengers work I felt was exactly the opposite. (Though to be fair, he'd found himself caught up in the whole Roger Stern/Mark Gruenwald/Avengers fallout, rather than shaping the book to his own vision by handling plotting, story and art.) But it's a fascinating premise, nevertheless: Would, for example, Ditko, Trimpe, Colan, either of the Buscemas, et al. have excelled as both writer and artist of a comics series? I continue to think that Starlin and Byrne may be the exceptions rather than the rule, but I'd certainly enjoy being proved wrong.

Murray, you raise excellent points in the parallels with the TZ and OL series; in relation to the FF book, my first thought went to the Skip Collins story which took place shortly after Byrne came aboard. And like yourself, I also couldn't see Doom and Masters (well, maybe Masters, depending on his free time) detailing every aspect of Liddleville--and yes, what if Johnny actually decided to go to New York like he was planning? Talk about the big apple...

Post a Comment